Mosborough: A Village Shaped by Time

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION

Mosborough is a village with deep roots — a place where history lingers in its lanes, fields, and old stone buildings. Once part of the parish and manor of Eckington, and now on the south-eastern edge of Sheffield, it has always been more than just an agricultural community. For centuries, the sound of hammer on anvil rang out alongside the call of the plough, for Mosborough was famed for a craft that shaped both its economy and its identity: the making of sickles.

Set some six miles south-east of Sheffield and eight miles north-east of Chesterfield, Mosborough lies just north of Eckington, the two separated by the winding Moss Brook. Its boundaries have changed little since medieval times, enclosing the hamlets of Halfway, Holbrook, Plumley, and Owlthorpe. A major shift came in 1967, when Mosborough was transferred from Derbyshire into the newly created Metropolitan District of Sheffield, South Yorkshire. Yet despite this administrative change, the village’s sense of place — defined by the valleys of the River Rother, Moss Brook, Short Brook, Ochre Dyke, and the wooded tributary near Plumley — has endured.

Though it once sat in a relatively remote corner of the county, Mosborough had all the natural advantages needed for industry: ironstone for smelting, grindstones for sharpening, and swift-flowing streams for waterpower. These resources supported a tradition of metalworking that stretches back to the medieval and early modern periods. By 1624, the village lay within the six-mile jurisdiction of the Cutlers’ Company of Hallamshire, created by Act of Parliament to oversee and protect the region’s skilled trades.

The making of sickles and hooks became the lifeblood of the village. In 1830, the writer and social commentator William Cobbett travelled through Mosborough and observed:

“The whole of the people… are employed in the making of sickles and scythes… they are very well off even in these times. A prodigious quantity of these things go to the United States of America.”

Sickle making was a precise and physically demanding craft. Forging, grinding, and handle-making were often carried out by different specialists, each stage requiring skill honed over years of work. Over time, small workshops gave way to larger manufacturers, yet the essential methods changed little. Eventually, agricultural mechanisation and international competition brought the trade into decline, but its legacy — in stories, skills, and surviving tools — remains part of Mosborough’s heritage.

The decline of sickle making in the nineteenth century coincided with the rise of other local industries. Coal and ironstone mining, along with brick making, brought fresh opportunities and a wave of temporary workers in the 1860s and 1870s. Yet through all these changes, the resident population remained steady, and the village retained a remarkable sense of continuity.

This book is an exploration of that continuity — of the people, trades, landscapes, and events that have shaped Mosborough across the centuries. It is a story of adaptation and resilience, where the rhythms of rural life met the clang of industry, and where the past still leaves its mark on the present.

CHAPTER II: BEFORE THE CONQUEST

Mosborough rises on a ridge some 120 metres above sea level, a commanding position that looks out across the Moss and Rother valleys. Such a vantage point made it a natural place for people to gather, settle, and defend — long before the village became part of Derbyshire and, much later, Sheffield.

Archaeology offers us only fragments, but even these glimpses are evocative. Flint tools — including a scraper found on Ridgeway Moor in the 1960s and others north of Eckington — hint at ancient hunters or travellers passing through. Perhaps they paused here, sharpening tools or resting before moving on, leaving behind these small traces of their lives. Aerial photography adds further intrigue, revealing the faint outline of a great circular enclosure in fields south of Plumley. Its age is uncertain, but its scale suggests that long before written history, people were shaping this landscape.

In more recent excavations at Staveley Lane, archaeologists uncovered a circular ditched enclosure some 80 metres wide, with evidence of iron smelting, forging, and even possible domestic occupation. Was this Iron Age, Romano-British, or early medieval? The answer is not yet clear, but such a site is rare in Derbyshire. If confirmed, it would mark the Moss Valley as home to some of the earliest communities in the region.

The Romans too left their imprint. A road, probably branching from the great Ryknield Street, is thought to have cut through Eckington and Mosborough. Its ghost lingers in local names. “Streetfield,” a common field recorded in Mosborough, carries the Old English word straet — a direct echo of the Roman paving stones. Sixteenth-century court rolls speak of land “in the Streetefeld,” alongside references to a “Street Yate,” a gateway on the route. These records suggest that Mosborough’s High Street still follows the same ancient line first laid down nearly two thousand years ago.

Coins scattered across the fields tell their own story of Roman presence: a sestertius of Hadrian, another of Faustina Junior, a denarius of Domitian, and a coin of Magnentius. In 2008, a hoard of ten Roman coins was found near Eckington Cemetery, dating from the reigns of Domitian, Trajan, and Hadrian. Most remarkable of all was a discovery at Plumley Hall Farm in 2012: five silver denarii from the Roman Republic, centuries before the Empire itself. The first such hoard ever found in South Yorkshire, it raises the tantalising question of why Roman eyes were drawn to this quiet valley.

The next wave of settlers came from the north. In the ninth century, Viking armies swept into the region, leaving their mark on both land and language. The Danelaw system reshaped society, with land measured in bovates or oxgangs, a system still recorded in Eckington deeds as late as the seventeenth century. Place-names echo their presence: Hackenthorpe, Owlthorpe, Westthorpe, Netherthorpe, Waterthorpe, and more — all carrying the Norse word thorpe, meaning farmstead. Owlthorpe may once have been Haldenthorpe, “the farm of the half-Dane.” Even the earthwork called Danes’ Baulk whispers of their occupation.

By 944, the Anglo-Saxons had reasserted control. Yet the Danish presence endured, woven into the fabric of the community. An Anglo-Scandinavian underclass remained across north Derbyshire and Yorkshire, their identity caught between two worlds. When the Normans arrived a century later, they faced not a simple Saxon countryside, but a land already shaped by layers of conquest, settlement, and resilience.

CHAPTER III: THE BOUNDARIES OF THE OLD VILLAGE

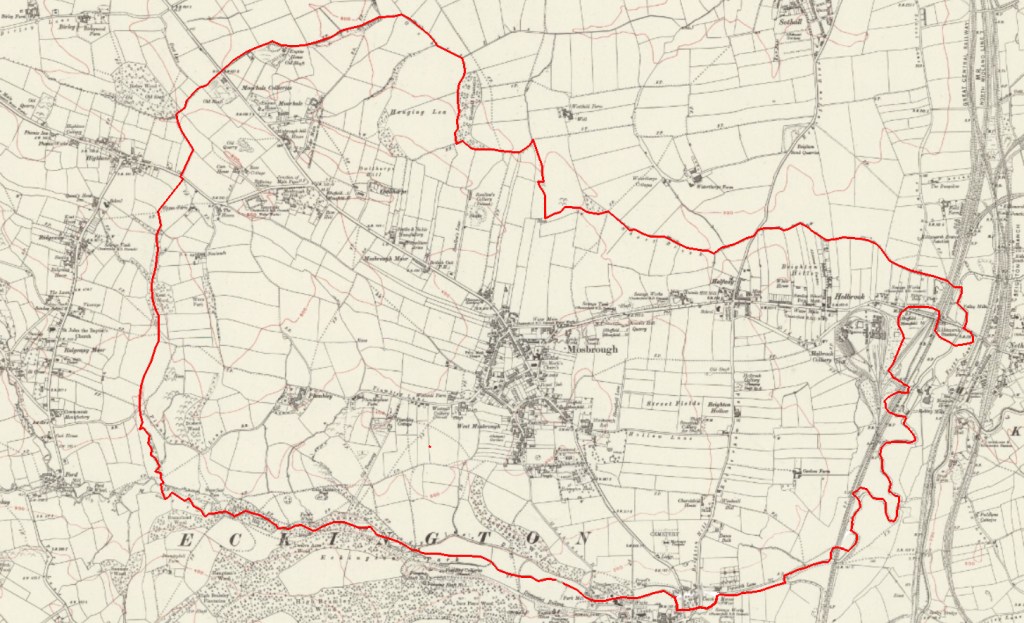

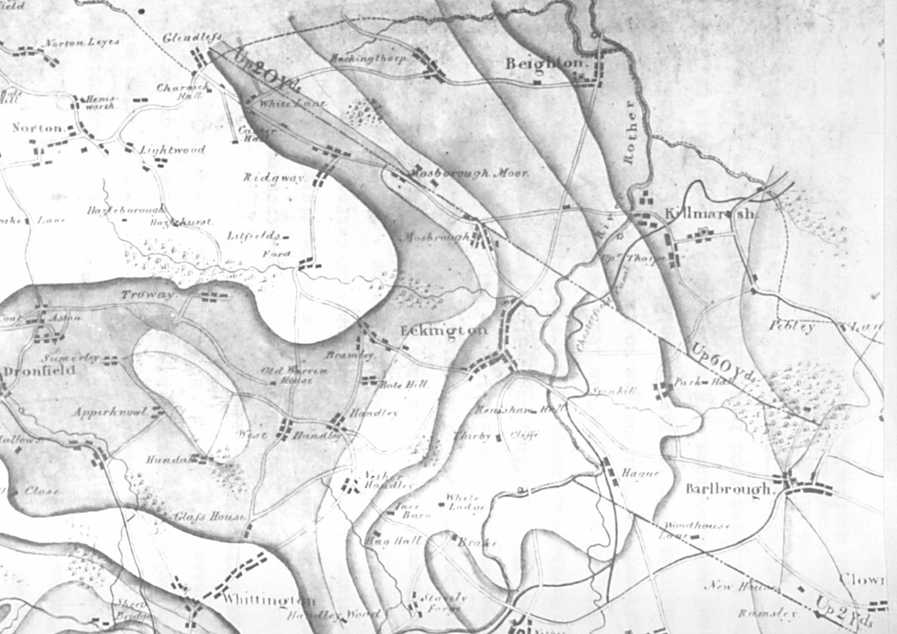

In the nineteenth century, trade directories often described Mosborough as “the township and straggling village,” yet in earlier times it was far more than that: it was an ancient manor, with boundaries that were not only clearly marked but also fiercely protected. Until 1967 it lay firmly within Derbyshire, before boundary changes brought it into South Yorkshire. Its lands spread across the south-facing slope of the Rother Valley, looking down towards the river as it wound its way from Eckington, where the Moss Brook joins it, towards Beighton and the smaller stream of Short Brook flowing from Halfway.

To trace the outlines of the old village (Figure 1) is to walk through both history and landscape. The starting point lies where the Moss Brook meets the River Rother. From here, the boundary runs west, climbing alongside the tree-shaded Moss. Even today, the course of the brook makes the old division clear. It passes beneath Rotherham Road and Sheffield Road, near the site once occupied by the old Atco works, and then winds on through fields north of St Peter and St Paul’s Church at Eckington. Here, by Mill Road, stood the manorial corn mill — now gone, but once a place of grinding grain and gathering news. At the Gashouse Lane junction nearby is one of only two ancient bridges linking Eckington and Mosborough, a reminder of how closely bound the two places have always been.

Westwards, the boundary continues with the Moss, past Cadman’s Wood and upstream towards the Carlton Wheel — once a water-powered grinding wheel — and the Seldom Seen Engine House, now preserved as a Scheduled Monument. The Engine House, with its brooding industrial presence, once served Plumley Colliery and may have housed a winding engine for its shafts.

Beyond Carlton, the Moss threads its way through Bowcinder Hill and Twelve Acre Wood, woodlands that in the Middle Ages marked the northern edge of Eckington’s great deer park. Deeper still lies the evocatively named Neverfear Wheel, with its millpond. The name itself captures something of the grit and determination of the sickle grinders who once laboured there. Across the fields leading to the wheel, the ghostly tracks of old paths can still be traced — the routes along which Mosborough grinders led their patient donkeys, panniers laden with blades ready to be sharpened.

A little further on, the ancient boundary leaves the Moss and turns north, following the Norbrook, a small tributary under Plumleywood Lane and towards Kent Wood. Near Newlands, the stream divides, and the line of the manor follows the eastern fork, climbing to its source at the top of the wood. From here, it no longer clings to streams but begins to follow hedgerows — west of Haven Farm, towards High Lane at the edge of Ridgeway village. High Lane was once the main highway from Gleadless and the west into Mosborough, and the crossing of this boundary would have been both practical and symbolic.

From Ridgeway, the boundary crosses eastwards, skirting the edge of modern Ribblesdale Drive, and picks up another tributary, this time feeding into the Ochre Dyke. Climbing towards Birley Wood, the line reaches one of its highest points before swinging east to follow the Ochre Dyke itself. Here the manor met the lands of Beighton, and the brook also formed the northern edge of the old ecclesiastical parish of Eckington. The neat, regular pattern of fields nearby speaks of the great Enclosure movements of the late eighteenth century, when the old open common of Mosborough Moor was parcelled out, reshaped, and reimagined, leaving a landscape that is still recognisable today.

From Birley Wood the boundary meets Moor Valley Road — once a busy turnpike between Sheffield and Mosborough. South of today’s Birley Moor Garden Centre it rejoins the Ochre Dyke, first running north-east to Hackenthorpe and then swinging south-east to skirt Hanging Lea. From here, a tributary of the Ochre Dyke leads it due south between Hanging Lea and Westfield Plantation, curving eastward towards modern Moss Way. The line then follows field boundaries south until it meets the headwaters of the Short Brook. Today the brook flows through new housing estates near Shortbrook Primary School, where once the fields of Waterthorpe Farm spread across the landscape.

It is still possible to follow the Short Brook’s wooded course down to Holbrook. The stream threads beneath New Street, under Rother Valley Way, past the old brickyards (later Massey Truck Engineering), under the Midland Main Line railway, before finally meeting the River Rother at the southern edge of what is now Rother Valley Country Park.

From this point, the manorial boundary takes its final sweep: along the northern bank of the River Rother, shadowing the railway line southward, until it returns full circle to the Moss at Pipworth Lane — where our journey began.

In common with many areas in England, the survival of local documents from the centuries before the Industrial Revolution is patchy. However, the archives of the lords of the manor, held in the private collection of the Sitwell family at Renishaw Hall are remarkably comprehensive. The Manor Court Rolls, edited by H.J.H. Garratt, have been published in three volumes to cover the periods 1506-1589 (Volume III), 1633-1694 (Volume IV) and 1694-1804 (Volume V) and can be consulted at local libraries. Sadly, it is unclear when or if Volumes I and II will ever be published.

The most rewarding collection of archival information is available for public inspection at Derbyshire County Records Office. Other medieval records can be inspected at Sheffield Archives, Staffordshire Record Office (for the ecclesiastical records of the Diocese of Lichfield and Coventry) and at the National Archives at Kew (which are increasingly accessible on-line through their website). The Local Studies Departments at Chesterfield and Sheffield public libraries have extensive collections of relevant printed material, particularly local will transcripts and memorial inscriptions from Eckington churchyard.

These archival records take on additional significance where they can be related to features on the ground. Take for example the tiny hamlet of Plumley, a corruption of the name for a plum-tree clearing, recorded in 1236. Cadman Wood, down by the Moss Brook, takes its name from a local family, probably Nicholas Cadman of 1543, and close by Mosborough Hall is the Old Hall, a gem of a building once occupied by Michael Burton of Cartledge Hall, Holmesfield, and later of Mosborough.

While such physical attributes of Mosborough’s history are of immense interest, they arose within the context of the community’s social, economic and political structure. One important part of that context was the parish church at Eckington. and, in particular, the medieval Parish Guild of St Mary founded in Eckington in 1310, reconstituted by Royal Licence in 1392 as the Guild of the Blessed Mary and Holy Cross and dissolved in 1547-8 by Henry VIII. It was one of many similar Guilds in churches across the country that came together for religious purposes, made up of leading members of the community, and becoming a major landowner in its own right through the charitable donations of its members.

[1] Cobbett, W., Rural Rides, vol. II, 609

Location

The township of Mosborough occupies some 2,200 acres immediately to the northeast of the parish of Eckington in Derbyshire.

In 1837 the village, then part of the ecclesiastical parish of Eckington, was combined with 33 other Derbyshire parishes to form the Chesterfield Poor Law Union[6]. The Union was given additional responsibilities by the Public Health Act 1872 and the creation of the Chesterfield Rural Sanitary Authority. This Authority continued in existence until 1894 when it became the Chesterfield Rural District Council under the provisions of the Local Government Act 1894. In 1974 Eckington (including Mosborough) became part of North East Derbyshire District. Sheffield City Council has administered Mosborough since boundary changes in 1967.

A County Council Order establishing the Eckington Parish Council in 1894 divided the parish into four wards; Eckington, Renishaw, Mosborough and Ridgway. Among the functions it assumed were those of the Eckington Burial Board, established in 1874. In 1896 the Lighting and Watching Act was adopted for the Eckington Ward. In 1936 the Act’s provisions were extended to include portions of the Mosborough and Renishaw wards, and in 1946 it was extended to the whole parish[7].

Ecclesiastically, Mosborough formed part of the ancient parish of Eckington until 1929 when it was created a separate new parish[8] with a church dedicated to St. Mark. It was transferred to the Sheffield Diocese on 1st January 1974[9].

[1] The Will of Wulfric Spot (1002 A.D.) lists Mosborough alongside other estates, subsequently recognised as manors in Domesday: “And I bequeath to Morcar the estates aet Walesho (Wales), aet Theogendethorpe, aet Hwitewylle (Whitwell), aet Clune (Clowne), aet Barleburh (Barlborough), aet Ducemannestune (Duckmanton), aet Moresburh (Mosborough), aet Eccingtune (Eckington), aet Bectune (Beighton), aet Doneceastre (Doncaster), and aet Morlingtune. And to his wife I grant Aldulfestreo just as it now stands with the produce and the men. And I grant to my kinsmen Aelfhelm the estate aet Paltertune (Palterton), and that which Scegth bequeathed to me.”

[2] Local Government Act, 1958, Sheffield Order, 1967.

[3] This was probably the site of the mill mentioned in Domesday, Stroud, G., Derbyshire Extensive Urban Survey, Archaeological Assessment Report, Eckington, 1999.

[4] Described in 1583 as “Norbeck”, Special Commission appointed 18th June 1853. DAJ, Vol. 38, p. 189.

[5] An Act for Dividing and Inclosing the Commons and Waste Lands, Common Fields, and Mesne Inclosures, within the Manor and Parish of Eckington in the County of Derby, 3 Geo. III, 1795.

[6] Poor Law Amendment Act, 1834.

[7] D.R.O., D453/

[8] Youngs, F.A., Jnr., Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England, 1991, p. 80.

[9] London Gazette, 18th December 1973.

Geology and geography

The land of the township rises fairly regularly from about 150 ft above sea level in the Rother Valley to the south-east to a maximum of around 600 ft at Moor Hole in the north-west on the border with Beighton. Because of this difference in height over a short distance, the streams and rivers were a source of water power from early times. Mosborough is drained by the Moss Brook in the south and the Ochre Dyke and Short Brook in the north, all flowing into the River Rother to the south. Celia Fiennes, referring to the passage of the Moss Brook through Eckington in 1697, observed:

“through it runns a Water which Came down a great banck at the End of ye town like a precipice with such violence yt it makes a great noise, and looks Extreamely Cleare in the Streame that gushes out and runns along: it runns on off a deep yellow Coullour, they say it runns off of a poisonous mine or Soile and from Coale pitts; they permit none to taste it for I sent for a Cup of it and ye people in ye Streete Call’d out to forbid ye tasteing it, and it will beare no Soape so its useless”[1].

Apart from alluvium gravels and sand in the valleys formed by the Moss Brook and the Rother, the whole of the township lies on the Pennine Middle Coal Measures. a sedimentary sandstone formation. These strata were extensively exploited for small-scale mining from at least the 14th century, ending with the closure of the collieries in the 20th century. Ironstone and clay in the Coal Measures have also been worked for iron smelting and brick making[2]. The presence of the Parkgate and Silkstone sandstone rocks also gave rise to quarrying over a long period. The Silkstone rock is folded by the Norton-Ridgeway Anticline at Mosborough. The outcrop edge forms the prominent high ground (‘the ridgeway’) from Mosborough past High Lane to White Lane End at Gleadless ( see Figure 4)

[1] Celia Fiennes, Through England on a Side Saddle in the Time of William and Mary, 1888.

[2] Geological Survey. Map 1:63,360, sheet 100.

Population

A detailed discussion on the population of Mosborough is problematic because of the difficulty of isolating the township from its larger neighbour, the dominant parish of Eckington. Because Mosborough was just one “quarter” or “bierlow”, it is almost impossible to discuss the two areas separately except for a few isolated occasions. The early Census returns record the population of Eckington, but with no further division into its constituent townships. Eckington’s parish registers date back to 1559, but do not record place names until the beginning of the 19th century, by which time more reliable data becomes available from the national census.

There were 231 households in Eckington in 1563 and in 1670, 214 householders were assessed for the Hearth Tax. In 1676 the incumbent returned a figure of 1,200 for his parish, which seems to be a rough estimate of the total adult population. The total of 98 houses in Mosborough counted by Pilkington in 1778 is the earliest guide to the township’s population, which might be roughly calculated for that year at around 490.

In the first Census of 1801, there were 597 inhabited houses in Eckington parish, occupied by 2,694 people. The population increased fairly steadily throughout the 19th century, reaching over 4,400 by 1841. There was then a huge growth of population with the development of the coal mining industry, and it increased to over 6,000 in 1861 and almost doubled to about 7,800 in 1871. This massive growth rate continued to over 11,000 for Eckington as a whole by 1891, slowing to around 12,300 in 1901. Most of this new population in Mosborough was concentrated around Duke Street, initially, followed by new housing at Chapel Street, Hill Side, Queen Street and the lower end of High Street by the 1890s. Some new housing also grew up along Cadman Street and Station Road and at Halfway.

Later figures were affected by boundary changes in 1967, since when there has been a massive expansion of new housing towards the north and east of the township, bringing the population of Mosborough to around 17,000 by 2016.

Communications

Until the late 18th century, the main road from Sheffield to Mansfield ran in a south-westerly direction across Mosborough Moor and through the village of Mosborough before descending into the Rother Valley to Eckington. George Sitwell described this early road in a letter of 1665 as “a great Road from the West partes of Yorkshire towards London”[1]. A Chancery deposition described it in 1692 as ‘the common highway from Sheffield to Gleadleys Moor, and so on to London, was by Little Sheffield, Heeley and Newfield Green, which appeared to be a very ancient way, being worn very deep’[2].

The construction of the turnpikes in the years after the passing of the Act in 1779 brought an improvement in communication which made the village more accessible for trade and enabled the ready movement of goods and produce, particularly coal.

Initially, the route was the modern one along City Road to Intake, Mosbrough, Eckington and Barlborough at Gander Lane, leading to Mansfield, where it joined the old Post Road. A tollgate was erected at the entry to the village in Mosborough High Street. In 1796, the road abutted directly upon the western entrance to Mosborough Hall[3], presumably at some discomfort and disturbance for the owner. By 1835, the road had been realigned at some distance to the west of the Hall[4], at the instigation, it was claimed, of Charles Rotherham, its owner in 1843[5].

In 1844, it was announced that the existing road from Mosborough Green, along what is now Station Road, through Killamarsh to Clowne, was also to be turnpiked[6]. A toll bar was located at Holbrook, and this enhanced road provided improved access from Mosborough to the Chesterfield Canal at Killamarsh. These toll bars were officially closed in 1896.

The Chesterfield Canal, opened in 1777, ran just outside the Mosborough boundary and close by the River Rother at Killamarsh. The upper section of the canal, which included Killamarsh, was closed around 1905 following the collapse of the Norwood Tunnel.

In 1840 the Midland Railway line was built between Chesterfield and Leeds via Rotherham and through Renishaw. It followed the Rother Valley along the eastern border of Mosborough and beneath Station Road at Holbrook, with a station at Renishaw, named Eckington Station. The station was replaced in 1874, later renamed Eckington and Renishaw station, which was closed in 1951. The Midland Railway was closed and decommissioned in 1975, and the route now forms part of the Trans-Pennine Trail.

[1] Riden, P., George Sitwell’s Letterbook, 1662-66, 1985, p. 192.

[2] Sitwell, G., Story of the Sitwells (n.d.), p. 56a.

[3] Eckington Enclosure Map, 1803, D.R.O., Q/RI/39.

[4] Sanderson’s Map, Twenty Miles round Mansfield, 1835, Part 1, p.8.

[5] Foster G., Reminiscences of Mosborough in the present century, 1886. This assertion may be incorrect, however, as Charles Rotherham did not acquire the property until 1843.

[6] Derbyshire Courier, 23rd November 1844.

Landscape and Settlement

It seems very likely that human activity in the area around Mosborough arose from the very earliest times. One of the oldest known sites of human occupation in England is but a few miles away at Cresswell Crags. These people left no written record of their presence, but evidence of their existence can be found amongst the artefacts they left behind.

Stone Age man has left evidence of his presence in the form of a significant known cluster of Mesolithic sites (c.8000 – 3900BC) around the flanks of an elevated ridge around Dronfield and Apperknowle, just a mile or so east of Mosborough1. Scatters of more than 4000 flint fragments were found sitting at contours between 110-190m above the valley floor of the River Drone. These were accompanied by cut features suggesting different phases of occupation. These sites conform to a general pattern found elsewhere in Derbyshire, comprising valley side locations which command expansive vistas across river valleys; features also found at Mosborough.

Evidence of Bronze Age (2200-700BC) settlement have also been discovered tantalizingly close to Mosborough, once again at Dronfield, where a site of some significance was found at Hall Farm and Birchen Lea Farm at Dronfield Woodhouse. Here evidence was found for two cairn burials consisting of cremations in inverted collared urns, along with substantial amounts of flint artefacts, including polished shale tools, and also a food vessel2.

In 2013, excavation in advance of residential development was undertaken at Staveley Lane, Eckington, which revealed part of a rural settlement dating from the Roman period. The settlement was occupied from the late Iron Age (100-50 BC) or early Roman period until c. AD 200. The enclosure was later used for an episode of iron smelting, which was dated by radiocarbon to the mid 7th-8th century. This was an extremely rare discovery, since a recent survey has identified only eight smelting sites in the entire country that date from the early and middle Anglo-Saxon period3.

The 1796 Enclosure Award map marks Mosborough Moor as a long strip of common waste, with a total of …. acres, on either side of the Eckington to Mansfield turnpike road, stretching from the parish boundary at the west end of the turnpike to the toll bar at Mosborough Green. It marks scattered farms and houses on the Moor’s edge, among which was Moor Hole Farm. On the south side of the Moor is mapped the location of Mosborough Hill, and about a quarter of a mile to the west, Haven Farm.

In the 18th century, settlement in Mosborough was distributed between several farmsteads and hamlets, none of which, apart from the village itself, was large enough to be described as a village. Burdett’s map of 1767 shows a cluster of houses along both sides of what is now High Street and South Street. Towards the east, Halfway is depicted as a house or group of houses at Station Road and Rotherham Road junction.

By the 1830s, there had been a good deal of development around Collin Green, School Street, Queen Street and Duke Street. The two sides of the village had become known as East and West Mosborough, respectively. There had been little new building elsewhere apart from a few new houses on Mosborough Moor, at Owlthorpe, and the Sickle Works there, along with Knowle Hill Corn Mill on Station Road.

By the 1870s, several rows of terraced housing had been built at Halfway, and more terraced houses appeared as infill along Queen Street, Chapel Street, High Street and Hillside. In particular, Eckington Hall had been built upon land on the turnpike road opposite Mosborough Hall. There were collieries at Westwell and Plumley, at Hollow Lane (then known as Mosborough Hall Lane), at Moor Hole, Holbrook and Swallow’s Colliery, and several disused workings4. There were two nonconformist chapels in Mosborough, a Methodist Primitive Chapel on Queen Street and a Methodist Wesleyan Chapel on Chapel Street, and new terraced housing at Holbrook, near the Colliery and Brickyard.

By 1914, a network of terraced housing had grown up in the angle between Queen Street and High Street, including Cadman Street and Gray Street and Stone Street between High Street and School Street.

(to be continued)

- Brightman, J. and Waddington, C., Archaeology and Aggregates in Derbyshire, A Resource Assessment and Management Framework, 2011, p 122. ↩︎

- Ibid. p. 124. ↩︎

- Allen, M., Young, T., Simmonds, A. and Champness, C., (2021),A Roman Enclosed Settlement with Evidence for Early Medieval Iron Smelting at Staveley Lane Eckington, Derbyshire Archaeological Journal, Vol. 138, pp. 61-91. ↩︎

- O.S. map, 1:10,560, Derb. XII.SE ↩︎