Long before today’s neat hedgerows and housing estates, Mosborough’s landscape was shaped by a very different system of farming — the open fields. The earliest permanent buildings were probably clustered around the site of Mosborough Hall, perched on the 127m contour line — the highest point locally — overlooking Mosborough Moor to the west. This commanding spot may even have been the site of the early English “fort of the moor”, from which Mosborough gets its name.

From here, the surrounding slopes were divided into great open fields, their layout still traceable in the shape of later enclosures and in the place-names recorded in manor court rolls and 18th-century maps. These fields weren’t hedged or fenced like modern ones. Instead, they were divided into long narrow strips, cultivated by different families under a shared, carefully regulated system. Each villager farmed scattered strips across different fields, sharing ploughing schedules, crop rotations and grazing rights.

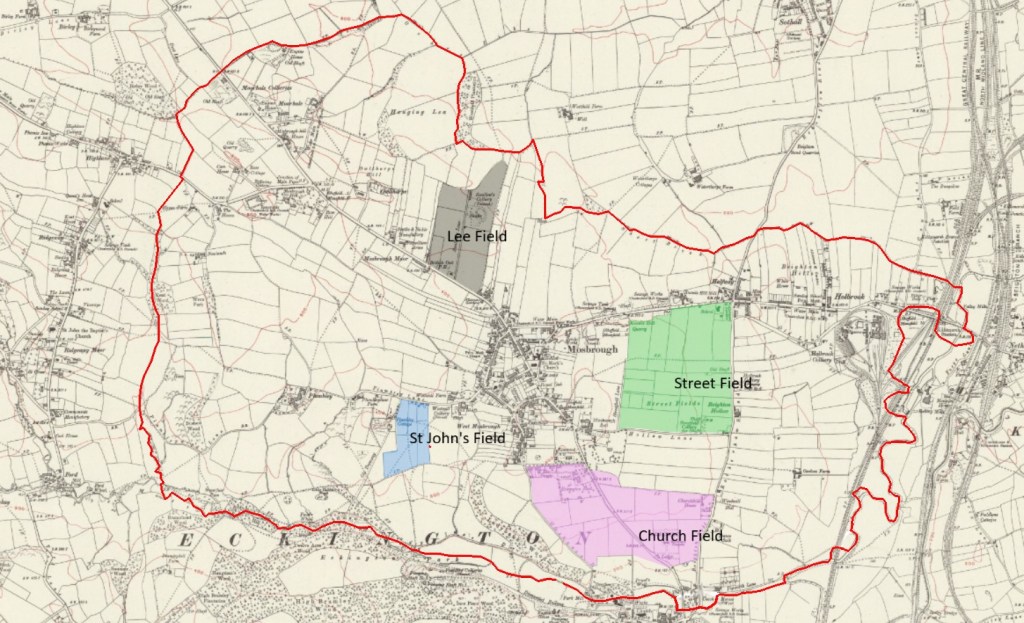

Three main fields surrounded Mosborough (see image attached):

Street Field lay west of Mosborough Hall, bounded by Station Road, Street Field Lane, Hollow Lane and Beighton Road. By 1795 it covered around 67 acres, divided between 18 occupiers. Parts of this land, including Swainhouse Field and Knowle Hill Field, had earlier been divided into smaller plots, hinting at centuries of cultivation. It has been suggested that the Streetfield name is associated with the Roman road, Rykneld Street.

Church Field stretched south towards St Peter and St Paul’s parish church. By the late 18th century, it was bisected by Sheffield Road and enclosed by Beighton and Park Mill (now Gashouse Lane) Roads, covering about 95 acres worked by 12 occupiers.

Street Field and Church Field were separated by a group of long strip-like fields running east to west, named Green Balk; “balk” in Middle English meaning an unploughed ridge of land separating fields. In a manorial survey dated 1480 Green Balk was occupied by Robert Rotherham of Mosborough.

Lee Field lay north of Mosborough Moor. In 1795, just two men – the Earl Fitzwilliam of Wentworth Woodhouse and Thomas Staniforth of Mosborough – held its 32 acres. Nearby “Harbour Friths” fields to the north, with their irregular shapes and woodland names, point to early assarts – clearings cut from the medieval woods.

Plumley had its own open field, St John’s Field, lying south of Plumley Lane and stretching down towards Lady Bank Wood. This 12-acre field was shared between four occupiers, and may correspond to “The Singels Field” mentioned in manor records of 1634.

Under the old open field system, each of these great fields would have been divided into strips and cultivated according to a communal crop rotation. One field might lie fallow while another grew winter wheat and a third spring barley or oats. After harvest, the fields were thrown open for common grazing, and livestock wandered over the stubble, manuring the land for the next year’s crop. It was a cooperative way of farming that tied the whole village together in a shared rhythm of work, decision-making, and landscape.

This ancient system survived here for centuries, gradually giving way to enclosure in the late 18th century, when hedges were planted, boundaries fixed, and strips consolidated into larger fields. But the names of Street Field, Church Field, Lee Field, and St John’s Field still echo the medieval past — reminders that beneath our roads and housing estates lies a landscape once ruled by communal plough and shared pasture.